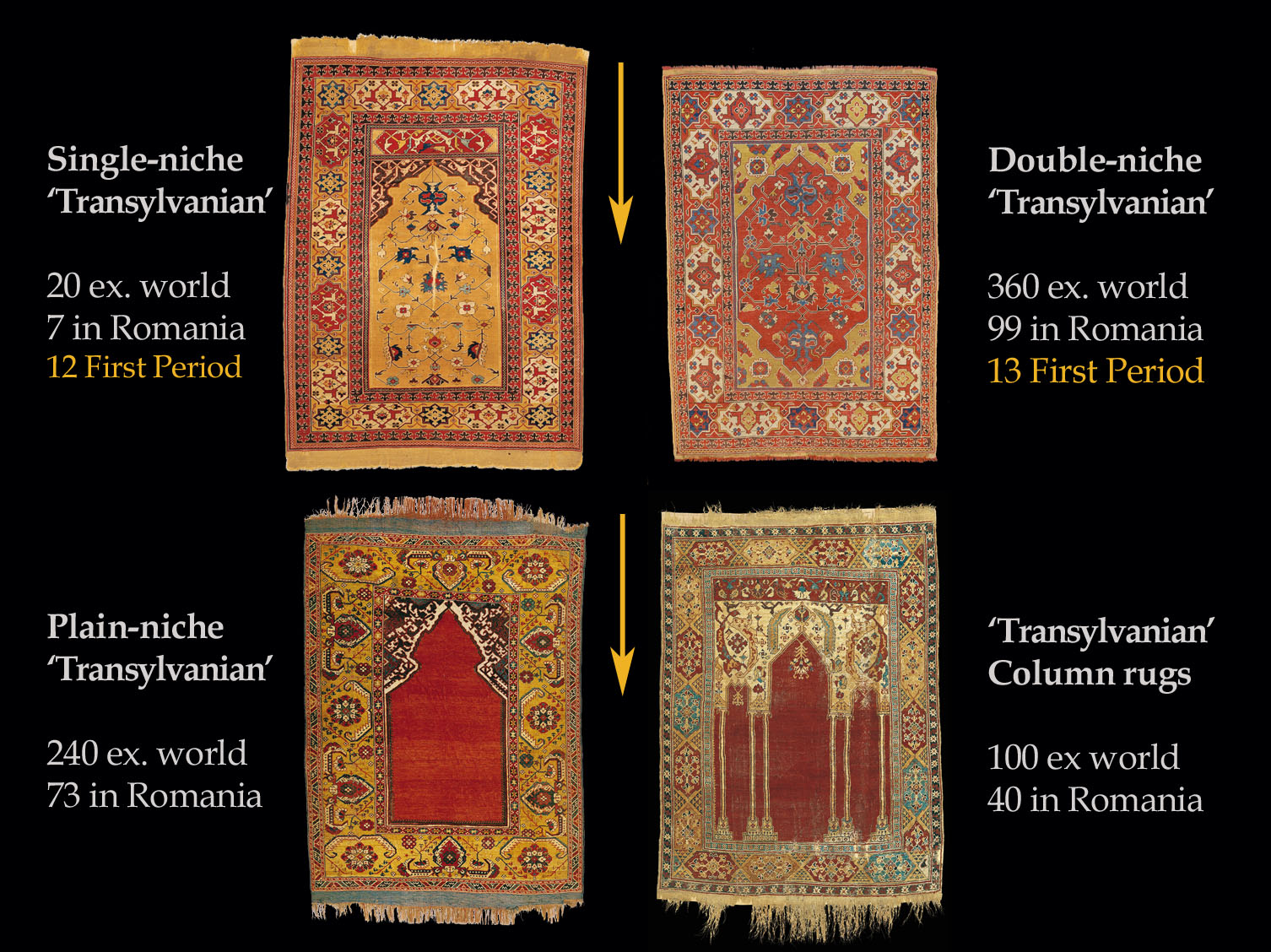

After the 100th anniversary of the great Budapest exhibition of 1914, when the ‘Transylvanian’ rugs were brought to the attention of the wider public, we had a fresh look at this fascinating and controversial group. According the design they can be divided in 4 main subgroups: Single- and Double-niche rugs (which should be discussed together), Plain-niche prayer rugs and Column rugs. These groups employ peculiar motifs for the borders and for the spandrels which suggest they were produced in different centres in Western Anatolia. The slide below shows the main groups of ‘Transylvanian’ rugs and their population world wide: about 720 examples survived today.

These rugs are all prayer format and reflect the technique of Western Anatolia weavings: wool on wool structure, lazy lines, weft color changes. In many cases we can observe stitched side finishings (which leave exposed weft). The absence of corner solution suggest the weavers did not follow a complete design. All the directional examples (except a couple of rugs) are woven upside-down which is a practical solution for making a well designed arcade. This is a relevant fact, which was somehow overlooked in the past. The upside-down technique is not encountered in Small Ushaks.

Together with the Lottos, the ‘Transylvanian’ rugs represent the largest surviving group of 17th century Anatolian carpets. Studying this group is fundamental for understanding much of the 18th and 19th century rugs of Bergama, Demirci, Dazkırı, Gördes, Karapınar, Konya, Kula, Ladik, Milas, Mucur, and even beyond to eastern Anatolia.

The key idea of this article is proving that the Double-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs evolved from the Prayer format with decorated field (usually called Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’). For long time it was thought that the forerunners of the Double-niche ‘Transylvanian’ were the Small-medallion Ushaks but as we will see later in this article this is very unlikely.

A shorter version of this post was published in an article on Carpet Collector magazine Nr. 3/2014 which can be downloaded from this link: Article.pdf (including German version Frühe Siebenbürger Nischen- und Doppelnischenteppiche) or English Article.doc; for any observation or additional information please contact the author at stefano_ionescu@yahoo.it

The Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’ Group

Origin of the Design

According to many authors the prayer carpet, called sajjada in Arabic, is the “most popular and widely used type of carpet” (R. Ettinghausen). The 17th cent. Anatolian prayer rugs with star-and-cartouche border and decorated field, with a mosque lamp hanging from the apex of the niche are called Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs.The study of the First-period examples is extremrly useful in order to understand the origin of the design. Only 12 First Period examples have survived until today, several in Transylvania but also in Turkey. They all show a very similar and well organised design, which points to a common prototype, today lost. All but one show arabesque spandrels.

Little was know about how this design came into being and how it was adopted by the provincial west Anatolian weavers. The lobed profile of the arch recalls the prayer rugs as those illustrated in 15th and 16th centuries Persian miniatures. The overall composition shows some similarities to 16th century Safavid or to Cairene prayer rugs and also to earlier works of architecture: the tiled mihrab with arabesque spandrels at the Tomb of Mehmet I in Bursa (built around 1420 by the ‘masters of Tabriz’) or the late 16th cent. Iznik tiled panel, at the Mausoleum of Selim II, in Istanbul.

According to recent research carried by the author, this layout – a mihrab topped by a Coranic inscription, surrounded by a wide cartouche border, framed by reciprocal motifs – recalls the 16th century Ottoman stained glass inner windows of the quibla wall of some of Sinan’s mosques. This is the case of Süleymaniye Mosque, Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque or, as Prof. Gulru Necipoglu points, to the Tomb of Şehzade Mehmet, where the original windows survived.

The same design is found in a miniature from Surname-i Hümayun of 1582, showing the Glaziers during the Parade of the Artizans. The fact that 9 (out of 12) first-period Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs have white or yellow ground is again compatible with this idea. Decorative elements, as the reciprocal trefoil border and even the chain-like minor border are employed in the Iznik tile revetments of the same period, as those found at the Sultan’s Tomb at Suleymanie.

All this suggests that the Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs (which lack a forerunner in carpets) derive from the Ottoman court style of the second half of the 16th century.

Surviving First-period Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs

Here are a few facts about the 12 surviving First-period Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs.

WHITE SP

Examples with Decorative Cross-panel

Six examples show a decorative cross panel above the niche. The earliest and the best one is the Single-niche from Sibiu, now in the National Brukenthal Museum. With 2500 knots/sq dm this is the finest ‘Transylvanian’ rug and probably the closest to the ‘ideal’ prototype, now lost.

The Sibiu rug was first published in b/w in the catalogue of the 1914 Budapest exhibition as cat. 73 . Then it was shown in color in Végh and Layer 1925, pl. 11, which was republished as Turkish Rugs in Transylvania in 1977 by Fishguard with a text by Marino Dall’Oglio who dates it to the “very early” 17th century. Notably the plates of the Végh and Layer 1925 have been used by Tuduc as models for his fakes. Such copies of the Sibiu Single-niche have been published in Schmutzler 1933, pl. 43, and Wulff 1934, pl. 15. Several other fakes of the Sibiu Single-niche rug, including one in Sighişoara inv. 540 one in a private home in the area of Braşov, and one in the Jim Dixon collection have been identified by the author.

More recently the wonderful Sibiu Single-niche rug was exhibited in Rome (2005), Berlin (2006), Istanbul (2007) and Gdansk (20013).

WIT

The field shows a mosque lamp hanging from the cusp and a scrolling vine with rosettes, flower buds, palmettes and simplified saz leaves. The composition is symmetrical along the vertical axis, with palmettes, of different types, alligned vertically. The motifs, borrowed from the Ottoman style are organised according to a precise design:

(1) an ascending palmette pointing to the mosque lamp;

(2) a pair of simplified split leaves above the palmette;

(3) two ‘rotating’ palmettes;

(4) a pair of four-petalled rosettes below the palmette;

(5) stylised saz leaves with half palmettes, at the bottom of the field;

An interesting feature of the Sibiu example is the cross-panel above the niche, with multicoloured arabesques on a brick-red ground. This motifs have been wrongly interpreted as confronting animals, but a closer examination reveals that they complete the spandrels’ pattern, displaying ivory arabesques on a dark ground. The well drawn star-and-cartouche border, flanked by reciprocal trefoil minor borders and ‘chain link’ stripes is typical for early examples. From the technical point of view this example stands out for the very high knotting density; there are no lazy lines are visible on the back but there are weft colour changes. The rug bears the donor name MICH Stamp, without any date. Research carried in the Parish archives could not trace the donor.

Additionally there are 5 Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs with arabesque spandrels and decorative cross-panel above the niche:

– the white-ground Avachian rug in the Museum of Art Collections in Bucharest;

– the Single-niche from the Monastery Church in Sighişoara inv. 536;

– the Ballard fragmentary rug in the SLAM (according to Tom Farnham it was bought from the Turkish collector Kafaroff around 1916); the author examined this rug and concluded that the historical restoration does not reflect the original.

– the Bensilum Single-niche (acquired by Herrmann from a collector called Bensilum who had bought it from Ulrich Schürmann), – the Achdjan-Tabibnia Single-niche (found in Paris long time ago), which is probably the latest in the group.

Examples with Inscribed Cross-panel

Three Single-niche rugs have a cross-panel with the same religious script. According to the Italian Ottomanist Luca Pizzocheri this translates: Hasten to the prayer before the death (comes).

The earliest Single-niche with inscribed cross panel is the well known Eskenazi-Dall’Oglio Single-niche ‘Transylvanian’ now. It has a very clear and fine design with fresh colours; the spandrels show a floral pattern with a stylised palmette, similar to the ‘scorpion’ of the Selendi rugs. The rug emerged in a collection in Lugano, then passed a number of owners and finally reached the Romain Zaleski collection in Milan.

WHITE SP

The angular design and the profile of the niche of the TIEM Single-Niche shown here, points to a later date, probably mid 17th century. Note the twisted ‘claws’ in the cartouches, which is a tendency towards simetrization of the motifs, which is one of the developments imposed by the need of weaving faster. The fact that it survived in a mosque confirms that prayer rugs with religious script were still produced for the local market.

A third example, with important restorations which probably do not reflect the original design in the central section, now in a Connecticut collection. This rug could have been purchased by Marino Dall’Oglio from Tuduc.

To the left, the rug from the Lutheran Church of Wurmloch now on display in St Margaret’s Church in Mediaş. It has the typical palette of the ‘Transylvanians’: red-ground niche, blue spandrels and yellow-ground border. The inner stripe does not show the usual reciprocal motifs, which are typical for the earliest examples.

Two other examples of this type are known so far:

MET 22.100.92, donated to the MET by Joe Mc. Mullan who acquired it from James Ballard who bought it in Istanbul, from a collector called Kafaroff;

MIA Doha, CA.96.2012 belonged to the Saxon collector from Braşov Emil Schmutzler. He published it as Plate 42 in the album Altorientalische Teppiche in Siebenbürgen of 1933. Today this rug is in the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, thanks to Michael Franses who acquired it in Sweden.

The Double-niche Layout

Given the apparent similarities with Small-medallion Ushaks it was thought that these were the forerunners of the Double-niche ‘Transylvanian’. This hypothesis is not supported by the motifs, which are all different, by the direction of weaving and by the color palette.

The reason why this layout came into being is probably related to a historical fact: the Edict sent in 1610, under the rule of Sultan Ahmed I, to all kadıs in Kütahya sanjak.

Here is the translation of Edict of Kütahya:

We heard that, weavers who produce carpets and seccades in your “kaza”s (townships), depicting mihrab, Kaba and hat (calligraphy) on carpets & seccades and selling them to non-Muslims.

Şeyhülislam (Shaykh al-Islam) prescribe this is against Islam and forbidden by şeriat.

In kazas you’re responsible, warn weavers about this fatwa to obey the rule: don’t depict mihrab or Kaba on carpets and seccades. If one doesn’t obey this fatwa, warn him sternly and send his name to us for punishment.

(Ahmet Refik, Istanbul Hayati (1000 – 1100), Istanbul, doc. 83, pp.43-44 Transl. by Levent Boz, Ankara)

So, producing rugs for export in the double-niche format was a way of ostensibly obeying the Edict.

When the second niche was added the field pattern had to be adapted and a second lamp was added. Most often the early Double-niche rugs are not perfectly symmetrical (on the horizontal axis) and in many cases there are clear directional elements (like the lamp in this case or the raising palmette in other). The idea of the double-niche could have been borrowed from Small-medallion Ushaks or from book-binding but all the design elements are peculiar to the Single-niche rugs.

Some people may object that in the 17th century Kütahya is known for pottery and not for carpet weaving. But as Levent Boz points, we should recall that Uşak was a kaza of Kütahya Sanjak! This clarifies why the Edict was sent to Kütahya, which was the capital of the Sanjak.

Here are other kazas of Kütahya Sanjak: Balat, Baklan, Banaz, Bozkuş, Çal, Çakırca, Dağardı, Dazkırı, Eğrigöz (Emet), Eşme, Gediz, Geyikler, Gılcan, Gököyük, Güre, Homa, İnay, Kazıklı, Kula, Osmaneli, Siçanlı, Silinti, Sirke, Şeyhlu, Tavşanlı, Uşak.

We should keep in mind that such regulation (fatwa) had to be observed by the weavers from other Sanjaks, like the nearby Manisa.

According to Vügar Dadaşov it is interesting that the fatwa (legal pronouncement of the Shaykh al-Islam and Mufti) to which Sultan Ahmed refers in his Edict, does not contain the word “mihrab”, but only Beyti Sherif (Kaba) and hat (khatt/calligraphy). But following to it, Sultan Ahmed orders (by mentioning that it is in accordance with the Fatwa-i Sharif) that “from now on, laborers (weavers) should not depict/weave 1) mihrab, 2) Holy Kaba 3) Hutut (various calligraphy) on prayer rugs… and they should weave as it used to be (“adet-i kadime” üzre (literally means “old traditions”)

WHITE SPACE

The close relationship between Single- and Double-niche rugs implies that they should be displayed and published the same way, with the start of the rug on the top.

In this way the ascending palmette is pointing up, all the upper part of the design matches with Single-niche rugs and the unresolved part of the vertical border (the truncated cartouche, if any) will be in the lower side.

Like all ‘Transylvanian’ prayer rugs Single- and Double-niche ones are woven “upside down”.

In the case of the Double-niche ‘Transylvanian’ from Skokloster Castle the design is almost symmetrical along the horizontal and vertical axis. Arguably the different shades of blue in the upper and lower spandrels could be a way of differentiating the niches.

WHITE SPACE

Star-and-Cartouche Main Border

A common element of all first-period ‘Transylvanians’ is the star-and-cartouche main border. The distinctive motif inside the cartouche is formed by two confronted split-leaves, usually red on a white ground, joined together to form a ‘shield’ which overlays scrolling flowers issuing from a central palmette. Similar motifs are found in 16th century Persian carpets or ceramic tiles. The star-and-cartouche border lacks a direct prototype among surviving knotted Ottoman carpets but layouts employing stars and cartouches, with floral motives or with Islamic script, are found throughout 16th century Mamluk carpets, Safavid prayer rugs and silk kilims and also in Islamic bookbindings, miniatures and architecture.

WHITE SPACE

Star-and-Star Main Border

WHITE

WHITE

Among the early examples it should be recorded a variant with less elongated cartouches, looking almost as a star-and-star border.

The field of the rug shown here is almost symmetrical but in order to differentiate one of the niches the weaver placed a supplementary stripe, like a base line, probably to point the bottom niche.

The color palette and the minor borders of this example are typical for Ushak area.

Two Single-niche rugs with star only border, but with large flower and feather leaf spandrels (which are later), survived in Transylvania in the Lutheran churches of Biertan and Blumenau.

Single-niche versus Double-niche ‘Transylvanian’ Rugs

The dating of west Anatolian rugs is supported by the inclusion of ‘Transylvanian’ carpets in Dutch paintings.

Generally only part of the carpet is visible; the carpet is in pristine condition which suggests it was new at the time it was painted.

The iconic star-and-cartouche border is documented after 1620, but usually it is not possible to discern between Single- or Double-niche rugs; but as the rugs invariably are shown on a table it is more likely that those were Double-niche rugs.

The earliest depiction of a ‘Transylvanian’ rug dates from 1620, Portrait of Abraham Grapheus by Cornelius de Vos; this correlates with the period of the Edict of Kütahya (1610).

The small part of the border and field from the Civic Guards Company of Captain Albert Coenraetsz Burgh, by Werner van den Valckert, of 1625 probably reveals a Single-niche example.

Later Examples (mid 17th cent.)

The overall layout of first-period ‘Transylvanians’ can be found in a few later examples where it is possible to trace the design changes.

The double-niche shown here is carefully executed but the profile of the niche looks stiff and there is a clear tendency to symmetry on both axis. To be noted the filling motifs added by the weaver in the spandrels and in the borders.

Another rug in a Hungarian private collection shows an almost symmetrical design, with central ascending palmette. Given the similarities of many details this rug was probably made by the same weaver as the Achdjan-Tabibnia Single niche.

In the rustic example of Black Church inv. 257 the design becomes angular, the motifs are misunderstood or lost but the overall pattern is still there.

By mid 17th century the design changed: the arabesque spandrels have been substituted by the large rosette and feathery leaves while the star-and-cartouche border became a cartouche only border. The demand for such rugs was probably high and the weavers made some changes in order to weave faster.

WHITE SPACE

Small-medallion Ushaks versus Double-niche ‘Transylvanians’

For long time the Small-medallion Ushaks have been considered the forerunners of the Double-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs.

Despite the similar layout there are major differences between the two groups which do not support this hypothesis.

Most probably the weavers in Ushak (which was in Kütahya Sanjak) observed the of the 1610 Edict: it’s worth mentioning that small-medallion Ushaks (with double-niche layout) are the largest surviving 16th century Anatolian rug group while there are very few (about a handful) of prayer rugs. (with one niche only).

For a complete survey of the Small-Ushak group we suggest to vistit John Taylor’s carpet blog, http://www.rugtracker.com/2015/09/ushakistan.html (plates 157-220).

Conclusions

In a next article we will discuss the composition changes of Second Period Double-niche ‘Transylvanian’ rugs, woven after mid 17th century, when this became one of the most successful patterns in western Anatolia.